1

State Shinto

Origins of State ShintoScholar Katsurajima Nobuhiro suggests the "suprareligious" frame on State Shinto practices drew upon the state's previous failures to consolidate religious Shinto for state purposes.

Kokugaku ("National Learning") was an early attempt to develop ideological interpretations of Shinto, many of which would later form the basis of "State Shinto" ideology. Kokugaku was an Edo-period educational philosophy which sought a "pure" form of Japanese Shinto, stripped of foreign influences — particularly Buddhism.

In the Meiji era, scholar Hirata Atsutane advocated for a return to "National Learning" as a way to eliminate the influence of Buddhism and distill a nativist form of ShintoIn the Meiji era, scholar Hirata Atsutane advocated for a return to "National Learning" as a way to eliminate the influence of Buddhism and distill a nativist form of Shinto.

From 1870 to 1884, Atsutane, along with priests and scholars, lead a "Great Promulgation Campaign" advocating a fusion of nationalism and Shinto through worship of the Emperor. There had been no previous tradition of absolute obedience to the Emperor in Shinto. This initiative failed to attract public support, and intellectuals dismissed the idea. Author Fukuzawa Yukichi dismissed the campaign at the time as an "insignificant movement."

Despite its failure, Atsutane's nativist interpretation of Shinto would encourage a later scholar, Okuni Takamasa. Takamasa advocated control and standardization of Shinto practice through a governmental "Department of Divinity." These activists urged leaders to consolidate diverse, localized Shinto practices into a standardized national practice, which they argued would unify Japan in support of the Emperor.

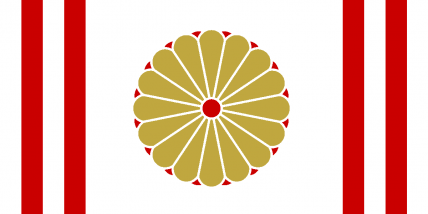

The state responded by establishing the Department of Divinity ("jingikan") in 1869. This government bureaucracy encouraged the segregation of Kami spirits from Buddhist ones, and emphasized the divine lineage of the Emperor from the Sun Goddess, Amaterasu. This action sought to reverse what had been a blending of Buddhist and Shinto practices in Japan. That department was unsuccessful, and demoted to a Ministry. In 1872, policy for Shrines and other religions was taken over by the Ministry of Education. The Ministry intended to standardize rituals across shrines, and saw some small success, but fell short of its original intent.

National Teachings

In calling for the return of the Department of Divinity in 1874, a group of Shinto priests issued a collective statement calling Shinto a "National Teaching." That statement advocated for understanding Shinto as distinct from religions. Shinto, they argued, was a preservation of the traditions of the Imperial house and therefore represented the purest form of Japanese state rites. These scholars wrote,

National Teaching is teaching the codes of national government to the people without error. Japan is called the divine land because it is ruled by the heavenly deities descendants, who consolidate the work of the deities. The Way of such consolidation and rule by divine descendants is called Shinto.

— Signed by various Shinto leaders, 1874

Signatories of the statement included Shinto leaders, practitioners and scholars such as Tanaka Yoritsune, chief priest of Ise shrine; Motoori Toyokai, head of Kanda shrine; and Hirayama Seisai, head of a major tutelary shrine in Tokyo.